The feminine judo players who won the gold during judo contests at the Olympic Games in Atlanta received titles strictly equal to those of the men's division. Japanese Ryoko Tamura, French Marie-Claire Restoux, Israelian Yael Arad and others are so well-known in their own countries that their fame is no longer restricted to the judo world. Their rise to the highest levels is emblematic. But, it cannot overshadow the obstacles women had to overcome to make their own way and establish feminine practice in a world dominated by male-defined standards and values.

History tells us about the place occupied by women. It appears to obey two opposite models. Women's attitudes and behavior either seem to be dictated by masculine patterns, or reveal their strong opposition to their social status, their quest for recognition. Looking back at the position women had in the judo world, two different periods are obvious. From the beginning of the century to the sixties, women have played nothing more than a minor role. Apart from rare exceptions, their autonomy was drastically reduced. The design of a women's practice, distinctive from the men's, was overdetermined by gender differences and life styles. From the sixties onwards a shift occurred in the social attitudes expected from women. Modernised sport-oriented judo became a field for women who demanded equal rights and access to judo contests. The way judo permeated western countries and spread all over the world explains how feminine practice evolved and differed according to places and societies.

In the early days of the century, Japanese combat techniques became famous worldwide. The amazing victories of the Japanese army during hand-to-hand fights puzzled observers, men and women. The Japanese method rehabilitated the use of a fair force. It was thus bound to appeal to the "new woman" fighting for her rights in the early days of the century. However, very few were then involved in martial arts. Women's practice reveals sociability patterns. Their techniques were constrained by the rules of decorum. Physical contacts, proper clothing and respectable attitudes had to be adapted to class behavior. The way women could exercise was closely defined by medical experts who attempted to ban sporting activities which allegedly jeopardized female reproductive functions. Whereas professional manuals for soldiers or policemen displayed crude self-defense techniques, those written for women clearly mimed violence. The stress was put on health and physical exercise.

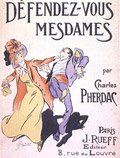

Still, although examples are rare, the emergence and the appeal of the Japanese method among women coincides with their struggle for autonomy. At the turn of the century, during the first wave of feminism, it was briefly used to fight the control of the dominant group in the struggle for suffrage. English suffragettes readily exploited the utilitarian side of jujutsu. They reportedly used jujutsu as a defensive weapon to fight policemen. The Japanese method was certainly seen as designed to pose a serious threat to the myth of female frailty. In 1912, prefacing, a French book entitled Defendez-vous Mesdames, the Countess of Abzac, begged modern women to acquire strength and freedom. She urged women to learn how to defend themselves. The appeal of the Japanese method among women was universal. The Fine Art of Jiu-Jitsu Emily Watts, from Great Britain, written in 1906, was prefaced by the Duchess of York. In the United States, Dennis Helm reports that, at the same time, Senator Lee's wife (grandson of General Robert E. Lee) and Mrs Wadsworth (relative of President Theodore Roosevelt) started to take judo lesson from Yoshiaki Yamashita. Many other examples can be given from Switzerland, Germany, Sweden.. The appeal of Japanese techniques of self-defense for women, no matter they are called jujutsu or judo, never flagged. They were quickly equated with autonomy and freedom.

In Japan, the art of fighting was a man's privilege. Here like elsewhere, physical education exercises for women were designed to make them healthy and improve their looks, to help them get ready for their future role of mothers. Many educators agreed : "Women are not meant to fight but to breed". Kano adopted the conception of the feminine body dictated by the scientific and medical theories of his time. The differences were biological. Kano did not want to overtax feminine bodies. He is said to have conferred with experts and judo medical science research personnel to make sure that the course of instruction and methods taught were right for women. "Develop one's mind and technique in harmony" was the motto of the women's section at the Kodokan. The stress was put on gentleness. The etiquette was strict. Ukemi was considered very important. Women were restricted in their randori. Any form of resistance was wrong. Kata practice was emphasized.

In the Kodokan archives, the first enrolment of women dates back to 1893. Miss Sueko Ashiya was recorded as the first girl to enter judo classes. Kano taught his wife, Sumako, and her personal friends. But, it is only in November 1926, that a women's section (joshi bu) was formally opened. The first woman to be awarded a black belt, in January 1933, was Katsuko Osaki. Noriko Watanuki,

Kano's eldest daughter was head of the women's section for many years.

Kano exerted every effort to internationalise his method. Traveling abroad, sending his leading disciples he organised the spread of judo. Slowly judo superseded jujutsu worldwide. With Kano's theories, the Japanese combat method acquired new scientific and educative dimensions. Women were also concerned by those changes but their practice was under the control of a teacher devoted to Japanese conceptions. In 1934, at Cherry Blossom as she says, Sarah Benedict Mayer arrived in Japan, staying until about April 1935. She was a member of the Budokwai of London and wrote a series of letters to her teacher, Gunji Koizumi, on her experiences. She met Kano and had lesons from Mifune. But, it was not before the late forties that women's judo started to become established and that women were gaining black belt status. After World War II, about 1949, Ruth Gardner from Chicago became the first non-Japanese female student to study at the Kodokan Institute in Tokyo, Marie-Rose Collet, from France, being the second. In Australia, in 1968, Patricia Harrington and Betty Huxley founded the first women's judo federation for the purpose of propagating Kodokan joshi judo. The Japanese example reinforced the beliefs of those who think strength is meant for men and aesthetics for women. Most of the time, women were taught by male instructors until some women became judo teachers. In California, Keiko Fukuda was instrumental in teaching a Kodokan-oriented women's judo. But, during the early sixties, Phyllis Harper voiced the leading conception of judo in the States. In an article entitled "Women's judo develops femininity", she affirmed : "Judo should be ladylike and should embody and exemplify the essence of the gentle way".

Because of the way Japanese hand-to-hand techniques are looked at, self-improvement through physical exercices and self-defense are the dynamos of the long interest women have had in judo. During World War II, elementary tricks were taught as "a basic escape training". In the relocation centers in the United States, women used to practice in order to keep fit and to be able to defend themselves. The evolution started in the sixties when women status in society changed and when judo began its shift into an international sport.

Rusty Kanokogi was the first female judo player to defy the rules of gender separatism. "I was considered an exceptional woman, a woman who played judo like a man". Pushing back her short hair, she entered the 1961 New York State YMCA championships. The world of judo, a traditionally male bastion, blatantly displayed its conservatism, the medal she won was taken away from her. The example of Rusty's judo career underscores the constraints currently imposed on women in the sixties, the prejudices of a male-dominated sport. Women had to fight for the right to fight. If, in the early fifties, female judoplayers were allowed to compete in some countries (France (1950), Morocco, then a French protectorate (1951)..), these isolated attempts were vain, and regularly ignored or laughed at. Up to then, women took part in grading contests but were denied the right to compete and obtain official titles. A new orientation appeared in the sixties in some European countries where tournaments were organized for female judo players (West Germany, Switzerland, Austria, then Italy, Great-Britai..). Judo as a sport no longer was a territory of virility to be conquered. On the contrary, female champions claimed equality as a right. Why should their participation be limited to technical tournaments or kata exhibitions? Female judo players of the seventies refused to be considered as a minority They demanded access to competitive meetings to be on an equal footing with men.

Mentalities evolved according to economic and social changes, but also with the number of medals obtained by women in international events, mostly when men's titles were harder to get. The rise of feminine judo reflects the general tendency and the debates of the seventies in favor of women's rights. It also reflects internal changes. The frame of reference was altered by the increasing sportive tendency. The International Olympic Committee's decision to include judo contests for men in the program of Tokyo's Olympics Games consequently allowed the definition of new finalities. Sport changed the scale of values and abilities. Progressively, the egalitarian perspectives of the coach replaced the gender-biased views of the judo master. To these internal evolutions must be added the effects of a consumer society which greatly influenced the motivation of judo players. The international culture of sport gradually replaced the Eastern culture of an educative martial art. Because of this growing tendency, the European Judo Union organised an experimental competition in 1974 in Genoa, Italy. The following year, in Munich, Germany, the first European judo championships for women took place. This decision and the first official titles awarded are all the more symbolic since in 1975 the year of women was celebrated. A similar evolution has been seen all over the world (first Oceanian women's in 1974, first Pan American women��s in 1976, first all Japan women's in 1978).

The first women's World Championships in New York in 1980, for which Rusty Kanokogi was largely responsible, and essentially the 1982 Paris Championships, radically erased the differences of the past. After the exhibition at Seoul, female judo has been part of the Olympics since the Games of Barcelona. In various countries, the number of members has significantly increased since female judo champions obtained World and Olympic titles. Statistics vary, but nowadays, women stand for roughly twenty percent of most color belts and about ten percent of black belts. Today, after Clare Hargrave from New Zealand, the first woman to be awarded the IJF "A" licence in 1981, there are female referees in both male and female international tournaments. In June 1998, in Berlin, Germany, 34 female referees from around the world joined the first ever seminar for women referees organized by the IJF.

Some female judo players have had their statues in Madame Tussaud's in London and in the Paris wax work museum, next to the best soccer players in the world. One century after Mrs Yasuda and her friends, the World and Olympic titles of Ingrid Berghams from Belgium, Cecile Nowak from France, Yamaguchi Kaori from Japan or Driulis Gonzales from Cuba underscore the equality of male and female judo players. This evolution was possible, mostly, because of pioneers who had the courage to fight traditions. It set up a chain reaction which compelled international judo to revise its models.

The place reached by women is linked to external and internal factors. The real causes of this evolution are numerous. Women's desire to have access to equal treatment, according with the policy to promote female victories and increase membership has challenged the cultural reluctance of certain countries. Women's participation is linked to the differences of finalism and values that distinguish a method of education from an international sport.

At six o'clock another contingent made an assault on shops in Regent Street, and fifteen minutes later Oxford Street was attacked. Mrs Garrud's jiu-jitsu school was just off Oxford Street in Argyle place and six of her Sufragette pupils were taking part in the stone throwing. [..]

Mrs Garrud's gymnasium was one of the bolt holes after the raid. She had taken up some of the floor-boards and covered over the gaps with heavy tatami mats. "They came back to the school because it was easy. They came straight in and turned those mats up. I made them strip off their outside clothes and give me their bags with their stones and any other missiles they had left over. All went under the floor-boards and back went the mats.

They were all in their jiu-jitsu coats working on the mats, when bang, bang, bang on the door. Six policemen ! I looked very thunderstuck and wanted to know what was the matter. "Well, can't we come in ?" said one of the policemen. I said : "No I'm sorry, but I've got six ladies here having a jiu-jitsu lesson. I don't expect gentlemen to come in here." He said : "Are they pupils ?" I said : "Yes, pupils." So, it ended up by one old man coming in and having a look round. He didn't see anything, only the girls busy working, and out he went again."

Antonia Raeburn, Militant Suffragettes, London, NEL, 1974.

I was born in 1871 and as I was weak in my youth I joined the dojo which was near our house. But, with the Russo-Japanese war I lost my teacher. Nethertheless, he had recommended to me a man named Kano Jigoro.[..] Afterwards, the Master taught me the yawara no kata (an old form of defense) and several defenses. After a month I began to study the falls and I repeated them for a month. Then, the following year, the Master suggested to me that we should climb Mont Fuji, the highest mountain in Japan, in order to judge our courage. We were five women and six men but, with one man, I was the only one to arrive in fairly good shape ; the others were fagged out. The next day, when I went to the dojo the Master invited me to practice and notwithstanding my protests on account of my fatigue, he bouted as strongly as usual. At the end, as he left me half dead with fatigue, he told me : "Take a bath and have some massage". This test proved to me that judo strenghtens woman both physically and morally.

On several occasions in my life I have saved people and myself thanks to judo. I have revived a carpenter fallen from a roof, left for dead by the doctor. I have saved one of my friends, almost drowned, and also left the same way. I have arrested an armed robber with my bare hands..

Kinko Yasuda, "Feminine judo", Judo, vol. V, n�� 1, January 1955

In a conversation with the late Prof. Jigoro Kano, he said to me, "I hope to spread women's judo throughout the world as widely as men's judo. Miss Fukuda, you must pursue the study of judo with this in mind". Naturally, those words of the founder of judo strongly impressed my young mind, and still remain vivid. Since then, I have endeavoured, in my own way to propagate women's judo. Perhaps, because of this effort, Prof. Kano often told men judoists, "If you really want to know true judo, take a look at the methods they use at the Kodokan joshi bu (women's section)". I am very proud of these words which have become a legend in the Kodokan. "Develop one's mind and technique in harmony" is taken as the motto of the women��s section, it is also important in men's training. [..]

The late Prof. Kano's ideal for women's judo was to study randori in parallel with kata. This randori must be done between women. I was instructed only in this manner for the first ten years of my judo study. Judoists in general spend many hours on randori. Although it is also true in women's judo, its characteristic is not to neglect kata while placing the importance on randori. This leads to the realistic methods of self-defense. This results in the increase of confidence in their everyday lives. Those who seriously study judo and master a higher degree of kata, may reach the point of acquiring "satori", comparable to that concept of "spiritual enlightment" in Zen Buddism, possessing a highly trained physique.

Keiko Fukuda, Born for the Mat, a Kodokan Kata Textbook for Women, 1973

Kano was taught jujutsu tenjin shin yo style from Keiko's grandfather Hachinosuke Fukuda. Keiko Fukuda and Masako Noritomi gave an exhibition of ju no kata during the Tokyo Olympics

It began in the fall of 1942 [..] A girl friend also was having a little figure trouble and when we discussed ways and means of doing something about our mutual problem, it suddenly occured to us that it might be smart to learn something about self-defense as well as to simply reduce [..]

About a year has passed since I first started at the Chicago Judo Club and in that time I had lost 35 pounds and was looking pretty good. The Club membership was dwindling fast. Most of our steady members had been either drafted or had volunteered into service. I took the fatal step myself and enlisted as an Air WAC [a member of the Women's Army Corps].

Later, in France I got my superior interested in judo. So, he approached the lieutenant who was in charge of special services and supplies. Alas, there were no mats. However, if we could get enough people interested in taking a course, perhaps they might be arranged. GI's, brass and even a French WAC caught on to the idea. About 10 women wanted to learn judo. A sour-faced sergeant summed it all up when he said, "We're fightin' a war. Military personnel are being bumped, but judo mats are being flown to you from England". The mats arrived and the classes began. The usual wholehearted enthusiasm was there on the part of all students, but only the most hardy and sincere stuck with it. We had classes split up so that I was teaching six nights a week. I could only teach what I knew, and soon came to the realization that a sankyu rating is not very high. However, my students were blissfully unaware of any shortcomings and the classes continued until our outfit began to move into Germany.

Ruth Gardner, "A Woman's-Eye View of Judo", in Robert W. Smith (edited by), A Complete Guide to Judo, Its Story and Practice, Rutland, Charles Tuttle, 1958.

At that time, applications didn't say "for men only", thought Rusty. She knew it was assumed that all players were male. She realized that her signature, "Rusty Glickman", wouldn't make anyone think otherwise. Pushing back her short hair and staying in the middle of her teammates, who wanted her with them and insisted that she had every right to be there? Rusty entered the gym and waited for her turn on the mat. When she stepped forward she thought she saw a few heads turn, but no one said anything. No one said anything when she won her match, either. But when she lined up with her team to get her medal, she was handed a note . The director wanted to see her.

"My teammates told me not to go", Rusty remembers. They said, "Stay in the line and get your medal and let him stew". But then it was a choice between being humiliated in public and being humiliated in private. I chose privacy, so I stepped off the line.

The director was furious.

"It wasn't an athletic thing with him", Rusty says. "It wasn't that he didn't think I could do it? obviously I could ! He didn't think women should. A woman just had no place there ?and he couldn't understand how I could have thought they did."

The former Coney Island Apache did not try to defend herself. She was afraid of being expelled from the class she was in at Brooklyn Central.

"It didn't say male on the application", she apologized. "If it had, I wouldn��t have entered."

After that, applications from the Y Association and the AAU had the word "male" on them, and Rusty was barred from competing.

Linda Atkinson, Women in the Martial Arts, Dodd, Mead &Co., New York, 1983.

1 comment:

I want just to say your blog and this topic are very good. Congratulations

Post a Comment